When I was a teenager, I began to feel this strange interior hunger, this longing, this flutter of the heart, a sensation I could hardly explain to myself. It was a sort of good haunting. I don’t remember choosing it, but I do remember that, sometimes when I would go to the local Barnes and Noble, I would look up at that mural of famous authors in the Starbucks and marvel at it.

In suburban Little Rock, Arkansas, this was my most sublime exposure to high literary culture.

We all have to begin somewhere.

Although, I will confess that even now I still get a thrilling sense of exhilaration if I’m ever back in some mall and look up at the mural again…

Back then, I wondered what those authors were talking about, but I also wanted to know, not just what they were saying, but how I could participate in that conversation, how I could internalize those thoughts and have those words become part of my being.

For the next several years, as I began to become more independent, I was driven by this strange desire, and I think it’s at the root of my wanderlust. I went to every symphony I could, although I had no idea what I was doing. I biked across Prince Edward Island with my friend, Jacob, to look at light houses on precipitous coasts. At one particularly loud coast, we sat there in awe for an hour, smiling into the wind and mist, and then turning to smile at one another. I went backpacking for two weeks in Alberta. We almost got eaten by a bear.

I bought a violin in Quebec City, which I hoped to learn to play. And, eventually, I got to Europe, where I drained my bank account on concerts and books and museum tickets (a fortune I had amassed by working as a retail salesman in a suit store, where I sold terrible tie-and-shirt combinations of my own invention: you have to start somewhere). I would also get lost in city streets at night. I didn’t have a smart phone, and, to my shame, I’ve always been terrible at directions, even though I’m an Eagle Scout (I got my troup lost in the woods once and the firemen had to come find us: nothing has changed since then). But back then, I didn’t really care. I would just start walking, in some random direction, and stop to look at things that interested me: walk into bookstores, discover churches, walk into that concert, stop for meals. I would do up to 10 or 12 miles a day, and when I was so tired I could hardly walk, I’d ask for directions to the nearest metro. I could at least get back from there. I did this in Paris and Genova and London and Rome and Prague and Budapest, because I wanted these cities to get into me, somehow.

I was now walking around inside the mural.

It was also at this time that I began to discover the ancient poetry of old Christian liturgies, with their dense poetic formulas and their artful repetitions (I still cry when I hear the “Exultet” at the Easter Vigil). It seemed to me that these hymns had somehow got into themselves the magic of old things, like ancient poetry (Horace or Pindar) and also the awe-struck gaze of the angels of the Old Testament. Whatever it was that these liturgies were trying to get at, they labored to express it and found their words, as artful as they were, inadequate. And so they had to start again, use another metaphor and add another rhetorical scheme.

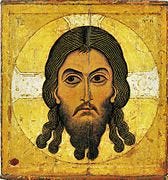

And then there were icons and portraits by Rembrandt and frescoes in Florence and the coast of Cinque Terre. I almost died there, too (see my “How to Die in Sardegna” for my most recent near-death experience).

In my mind, the hunger for all of these things (natural beauty, cities with long pasts, pre-modern poetry, icons, paintings, old poems in Latin or Greek or Italian, Easter vigils in the dark with candles and twenty-minute, sixth-century hymns ) were somehow connected. But only now, looking back on those experiences, do I think I can begin to touch with words what these things meant to me: I hungered for beauty, for depth. As Jacques Philippe has put it, despite all of the “progress” of modernity (and there has been some), we still experience within “an unquenchable need for the absolute and the infinite.” He adds: “We were not created to lead drab, narrow, or constricted lives, but to live in the wide-open spaces.” Our bottomless technologies try to satisfy this infinite yearning by producing an unending number of commodified pleasures and jokes and entertainments. But what we want is the whole and simultaneous possession of the fullness of life. That’s what Achilles wanted, and why he was hurt when Agamemnon offered him a pile of treasure in exchange (I write about this in my O.G. book, Falling Inward). Boethius called it Eternity. Dante said it’s what drives our lives and is the secret core of even our daily and small loves.

All of this is what I want to talk about in “Beauty Matters”: the Experience of Beauty.

I am interested in what beauty is, but I’m also interested in what it feels like and when the haunting of beauty comes upon us and how beauty can change our lives and how beauty can give us something to live for and how it was that the ancients knew so much more about it than we do.

I’m also interested in the vacuous sense of despair and depression that pervades our society, and why it is that the entertainment we consume on a daily basis leaves us as hungry as we were before (the spiritual equivalent of how we feel after eating fast food).

I’m interested in the “mechanization” of the world picture, the “datafication” of the soul, the crisis of masculinity, and our addictive relationship to technology: in a phrase, in why it is, as Byung-Chul Han put it, that “for us the experience of beauty is now impossible.”

Most importantly, I’m interested in the whole range of beauty: in nature, in music, in painting and sculpture, but also in cities, poetry, architecture, and even family life. I want to know why we call such disparate things beautiful: why would we say that—say, in some Terrence Malick film—a supernova or cavern in Utah is beautiful; but also say that the music of Palestrina or the mandylion face of Jesus is beautiful, as well.

As the readers of my books know, I rely, most often, on Dante, Plato, and Lewis (and, sometimes, Tolkien) to help me articulate what beauty is and what it feels like. I consider myself their disciple, and I have a loyalty to them, which is fired by a personal affection, despite the centuries. I feel about them the way I feel about my favorite teachers (my history and Latin teachers in high school, my Greek teacher in college).

And so, throughout these essays, I will attempt to bring together some of the things I’ve said before and will say again (here and in my future books).

What is beauty, then?

I’ll adopt this as working definition: beauty is the benevolent manifestation of the eternal within the temporal, a manifestation that reveals itself as an elevating order and in a profound display of power (I’ll try to explain that later). And so, when human beings experience beauty, we are “shocked” awake. It’s all in Plato. Every experience of beauty comes upon us “all of a sudden.” We feel a strange surge of life within and a longing to reach beyond our ordinary life and our merely mortal state. It’s almost a feeling of woundedness, an awakening to how our lives have been incomplete, hitherto. It’s analogous to falling in love. Beauty is unexpectedly full of life, longing, and surprise. It feels old and new, at once.

Ever ancient, ever new.

And that phrase—borrowed from Augustine, of course—will guide almost all of my reflections, because as Tolkien puts it, beauty feels like it comes out of a “deep abyss of time,” even if it it is new. Even if it was made by Paul Kingsnorth or James MacMillan or Wendell Berry or James Langley or Andrew Wilson Smith yesterday (more on these living artists, later), it will have a quality of weightiness and the smell of antiquity.

At the same time, old things, archaic things, when read or seen rightly, feel shockingly new and relevant and even urgent.

And almost all of my teaching and writing has been dedicated to trying to articulate that: the newness, the freshness, the “alive-ness” of even ancient things. Old things are new again. Beauty matters.

Ryan’s Wife here! 👋 Hi!!

So glad you are on Substack, Jason! I’m very much looking forward to your thoughts on beauty - and it’s something I’ve also discovered in my own life, this deep and essential need for beauty to refresh one’s soul.

I was only able to see the beautiful, ancient art & churches years ago (many of the same places & sights you reference above), but long to return again!

It’s also why I’ve become so attached to my current home parish - we’ve got a 100 yr old church with beautiful architecture, incense, bells, occasional Latin, communion rail. Growing up in a modern Catholic Church of the 90s, I had no idea what was missing from our style of worship - with so many past traditions stripped away. We had lost the “benevolent manifestation of the eternal within the temporal.”

Praying for your success, as you inspire more beauty with your words and ideas on this platform!

(1) You mention the "magic of old things," found in your beloved liturgical hymns... Is this "magic" the beauty you define at the end of this substack story? Or is it perhaps the harmonies of the spheres and echoes of the eternal paradigm? (2) You say, "I hungered for beauty, for depth." In the past I would have understood "depth" as complexity or something beyond my understanding, but now I wonder if you are referring to the "verticality," which I hear you talk about in other places. (3) Do ideas fall within the category of beauty? When you speak of the suddenness, shock, haunting, surge of life and even the wounding of beauty... I notice this experience and even speak of these same qualities when it comes to some ideas - for example every time you teach us about "intelligentsia," or first hearing about the demiurge and the eternal paradigm, or the soul being tuned by poetry... Are these living ideas connected to beauty?