I got a vision of hell today, here in Edinburgh airport, where I’m seated and writing, while waiting for my flight. Edinburgh airport is not particularly good (like Zurich) or particularly bad (like O’Hare or Newark). It’s just an airport. Like other airports, it’s a crowded, commercialistic, hurried non-place. It makes you nervous and irritable.

By design.

As my readers know, I borrow the term non-place from the Parisian sociologist Marc Augé, who defined non-places as “spaces of circulation, consumption, and communication” that have been engineered for the almost total reduction of resistance to the free flow of movement or exchange: moving walkways, escalators in public transportation hubs, light-rail trains connecting terminals, waiting rooms for medical services, interstate clover leaves, runways and tarmacs, hotel lobbies, hotel rooms, office cubicles, supermarkets, distribution hubs, suburban neighborhoods—in short, any space that has been scientifically engineered to optimize its efficiecncy, at the cost of absolutely everything else.

As soon as you are armed with this definition, you realize how much time we spend in non-places. They look like this:

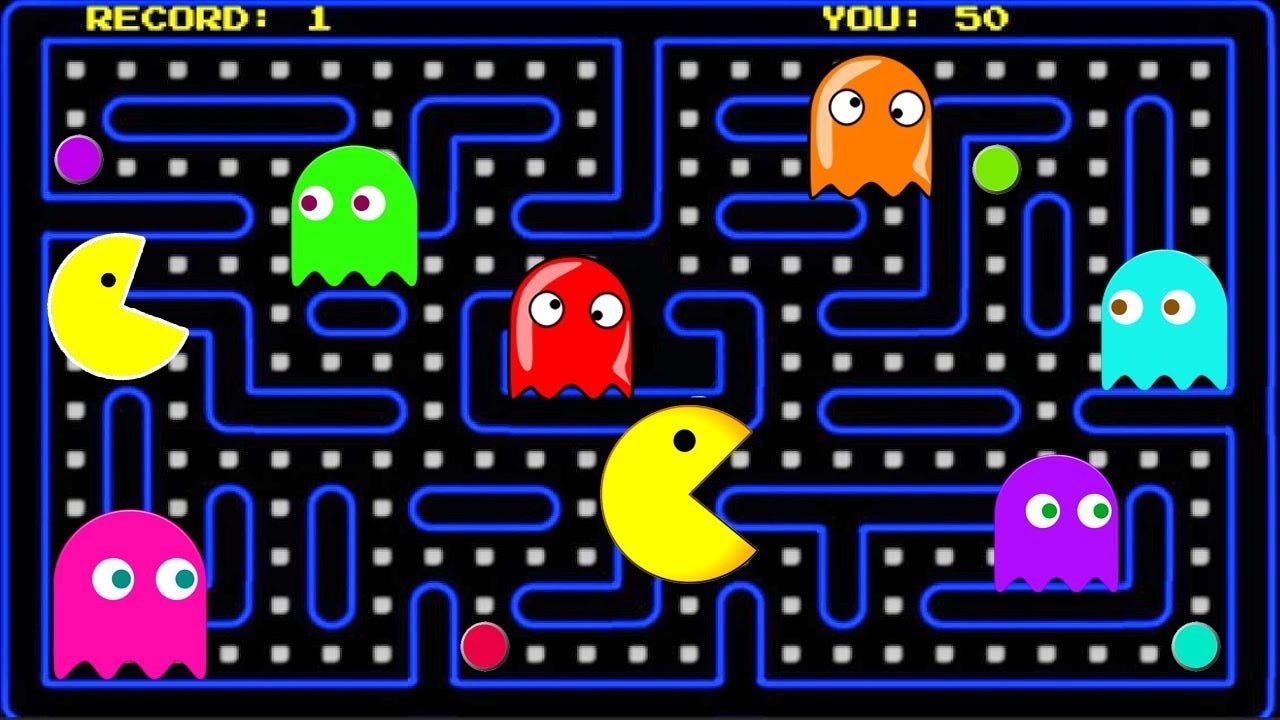

And they feel like this:

Non-places come at a high cost because all the other goods you might be able to find in “anthropological spaces” (history, ritual, serendipitous encounters with friends on piazzas, beauty, nature, architecture) have to be set aside in the single-minded pursuit of efficiency. Furthermore, Augé adds, our age is witnessing not only a proliferation of non-places but the linking of them into a great network, which creates an ever denser and ever more connected patchwork quilt of hyper-efficiency: “The same hotel chains, the same television networks are cinched tightly round the globe, so that we feel constrained by uniformity, by universal sameness, and to cross international borders brings no more profound variety than is found walking between theaters on Broadway or rides at Disneyland.” And this patchwork quilt of non-places is what Augé calls “supermodernity,” a better sociological term for our world than “post-modernism.” The impish and risqué French novelist, Michel Huillebecq, has made the cynical suggestion that one day the whole world will feel as placeless and communion-less as an airport lobby: “After the check-in formalities, I wandered around the shopping arcade. Even though the departures hall was completely roofed-over, the shops were built in the form of huts, with teak uprights and roofs thatched with palm leaves… All in all, airport shops still form part of the national culture; but a part which is safe, attenuated, one which fully complies with international standards of commerce. For the traveller at the end of his journey it is a halfway house, less interesting and less frightening than the rest of the country. I had an inkling that, more and more, the whole world would come to resemble an airport.”

Augé’s little book, with its thrilling title, Non-Places: An Athropological Introduction to Supermodernity, must have hit a nerve, because in the early 2000s it was, however unlikely, a best seller, translated into twenty languages. Non-Places has also become a source of inspiration for aritsts of all kinds across Europe, who have tried to use their crafts to make visible this almost invisible part of supermodernity. As British photographer Karl Childs puts it: “you wont remember them. You walk past them ever day. You've never given them much attention yet they occupy your every-day life. They are places visited only in transit. They are Non Places.” But his photography makes non-places unforgettable and recognizable. Indeed, after my “Experience of Beauty” class last fall at Benedictine College, my students walked around enthusiastically pointing them out to one another.

But as I was passing through the duty-free zone today—it takes a full seven minutes just to get through all the fluff and puff and glam—I all of a sudden had a vision: what if this went on forever? What if, as you walked by little samples of fake chocolate and assorted electronics, then continued on past smiling salesmen, who offer to spray perfume on your wrist, and then beyond those clerks who obligingly offer you any one of a thousand types of alcohol (all produced by the same company), all while listening to disco songs remixed to modern dance rhythms… what if it just kept going? The pulsing signs, with their unnaturally bright colors, would densensitize your prefrontal cortex, forever, and thereby awaken your inner desire for unlimited consumption, forever. The unending, strobing ads would promise pleasure, parties, power, speed, access to gorgeous bodies, but the pleasures would never be delivered. You would just keep walking and buying and getting perfume sprays and filling up large plastic bags and tasting gin samples, too small to satisfy, with the airy hope that somewhere down the line, after walking for an hour, a day, a year, a century, a millennium… then, you would find rest. But it would never come.

And that would be hell.

I had a similar vision the previous night in Edinburgh: the city center on a summer night was crowded with people who were there to let off steam, drink too much, attend semi-pornographic theater shows (somehow tolerated on account of artistic licence), and buy expensive tickets to vulgar comedy routines which promised a whole evening full of boring, dirty jokes. I saw streets littered with trash, encountered homeless people using drugs in the stairwells, and smelled urine everywhere. But what hurt the most was the idiotic bustle of crowds rushing here and there, in order to stop at the next station of consumption. Big cities are proud of their multiculturalism. And, sure enough, Edinburgh, even while commodifying the Scottish identity and selling fake versions of it, is full of Mediterraneans and Asians and Africans. In a similar way, the duty-free stores put up adveristemsents of Asian women deliriously laughing at the jokes of European males, while their South American friends look on approvingly. But this is not really diversity, is it? In this vision of the world, we are reduced to QR codes. Our origins, religions, skin tones, and cultural traditions do not hinder the rate of our consumption in the midst of non-places.

It’s a little bit of a paradox, isn’t it, that the conditions of affluence and comfort in supermodernity can create such moods of anxiety or despair? On the surface, you would think that being surrounded by thousands of bright and pleasing objects would elevate the soul rather than plunge it into self-distracting despair. But the paradox rests, of course, on the fact that what the soul thirsts for is deeper than any of these commercialized products: what we want is something infinite and whole. But when we whittle our souls down to our inner Pac-Man, whose jaws are forever opening and closing, trying to gobble up those little resource dots or pleasure points, we are trying to substitute for the infinite whole an unending chain of finite things: no matter how much it consumes, the soul is left feverish and hungry.

At this point, some of you are looking for the “unsubscribe” button. Alas, Substack only allows me to provide this button for you:

You: Why are you making so much of these banale experiences?

Me: I think it is because I’m just returning from my second trip to that charmed area along the Scottish and English borders that runs from Melrose, up over the Eildon Hills… down into the river valleys of the salmon-fishing Tweed and the forested Teviot… then up into the Scottish hills and down again into Yeltholm Town, where you can eat at the world’s last real pub, run by the conscientious Lynz (The Plough), full of dogs and locals who talk to you about books. This takes about four days of walking. But then you go through the little market town of Wooler, where you can buy, um, wool, then up into the forests where you can pray in Cuthbert’s Cave, the spot where the incorrupt body of the wonder-working saint rested before eventually being moved to Durham. But the glory of the route is, of course, crossing the Pilgrim Sands, preferably under the guidance of Gandalf himself:

After six days of hiking you’ll love the cold water that rests on the sands…

Just think how much you’d have to pay for such a therapeutic treatment in California!

In other words, I think I’m having a (spiritual) allergic reaction to the non-places that are, most of the time, invisible to us. Indeed, never within a twenty-four-hour stretch, have I been in two places more different. Yesterday, I went to bed in hell, but I had woken up on the Earthly Paradise

Me: Holy Island is the most beautiful place in the world.

You: Really? What happened to your much-vaunted Sardinia? Or Ischia? Or Umbria?

Me: Holy Island’s beauty is due in part to its intense combination of all the primal elements. Over the course of your week-long walk from Melrose, Scotland, along St. Cuthbert’s Way, you might walk by and over water in the Tweed Valley or enter into the rock of the earth among the caves in the hills. You pass through a series of separate landscapes, in which a single natural element is elaborated, like a movement in a symphony. But on Holy Island, all these elements come together: the undulations of the wind make rhythmical patterns in the grass and within the ripples on the water, while billowing clouds float leisurely across expansive skies…

You cling to the rock of the earth, while looking for the Prayer Holes, suspended over water, accompanied by the sound of wind and barking seals, surrouned by spongy, growing things...

The strangest experience of all for me was that, although I was only gone for a week, I felt like I had been gone for a year (my wife had the same impression, although for different reasons). Twenty hours on Holy Island felt like a month. Was that because I was running around, playing film director, phoning taxis, and making dinner reservations? Maybe. Or was it because on Holy Island you experience what Pavel Florensky calls “deep” time or “dense” time? Is this what we even mean when we say “beauty”: the suspension of time? The saturation of time with eternity?

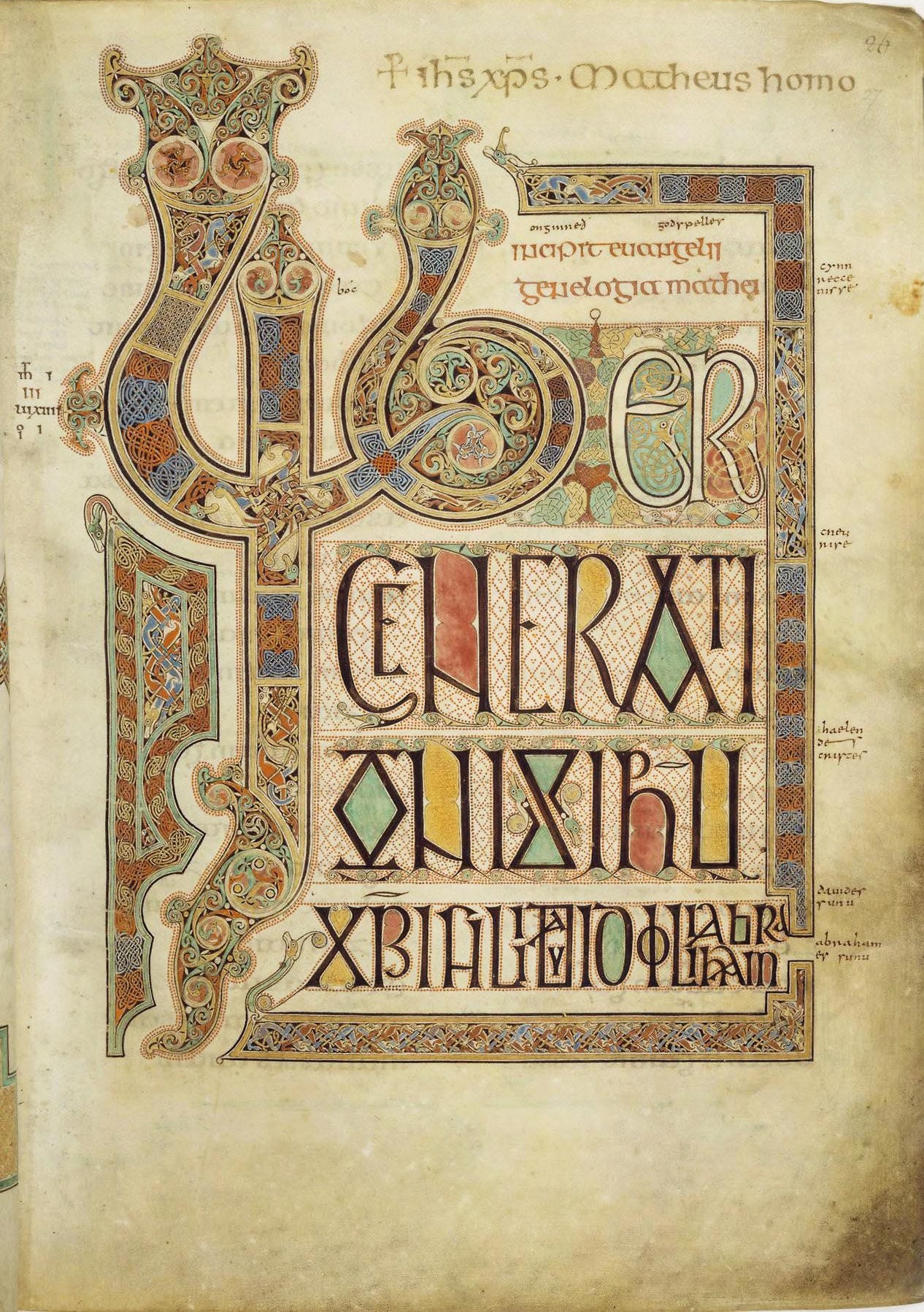

But, as ever, what excites me the most is the connection between these landscapes and the literature that grew up within them; in this case, how the ancient prayers—especially the loricae, or “breastplate” hymns, like “St. Patrick’s Breastplate”—tried to get into their poetry the rhythmical, repetitive patterns of the sea, or the rocking sway of blown grass, doing in words and rhetorical structures something analogous to what the Lindisfarne Gospels were doing in pen and ink.

Indeed, celtic prayers are famous for their “repetitiveness” and eleaborate structures. The beautiful and mysterious St. Brendan lorica takes thirty-five-minutes to get through! But here is a small part:

All holy angels and archangels, all patriarchs and prophets, all holy judges and leaders, all holy kings and Maccabees, all Holy Infants and Chosen ones of God, intercede for me.

May Christ’s nativity,

Christ’s circumcision,

Christ’s baptism,

Christ’s works,

Christ’s power,

Christ’s teaching,

Christ’s preaching,

Christ’s cross,

Christ’s passion,

Christ’s soul,

Christ’s flesh,

Christ’s spirit,

Christ’s resurrection,

Christ’s ascension,

The descent and advent of the Holy Spirit the Paraclete

Defend me from the cunning snares of the enemy. Amen.

All holy disciples of the Lord, and their holy successors, pray for me,

Holy baptizers,

Holy archbishops,

Holy bishops,

Holy priests,

Holy deacons,

Holy lectors,

Holy exorcists,

Holy doorkeepers,

Holy martyrs,

Holy confessors,

Holy virgins,

Holy anchorites,

Holy monks

Holy clerks

Holy layfolk

Holy wives

Holy lords

Holy servants

Holy rich

Holy poor

Holy teachers

Holy artisans.

May these and all the saints, with the perfect Trinity, be a breastplate for my soul and spirit and body, with all their parts within and without, from sole of foot to crown of head, for sight, for sound, smell, taste, touch, flesh, and blood, and for all my bones, nerves and innards, veins and marrow, limbs, and may they keep me from death. For through you, Lord, all my members are brought to life, are given breath, and are healed.

Protect me, Lord, on the right and left, before and behind, below and above, in the air and on the earth, in the water, on the sea, in the tide, in rising, in walking, in standing still, sleeping, waking, in every action, in every place, in every day, in every hour, in every night, in all my life.

Watch over me, come to my aid, triune God, God Almighty, Adonay, Araton, Osya, Eloy, Ely, Eloe, Sabaoth, Elem Eseria, Saddia, immutable Lord God, and also Emmanuel, Christ Jesus.

Now this is diversity. Doorkeepers can be holy. Poor people can be holy. Rich people can be holy. Priests can be holy. Bishops can be holy. Furthermore, the poet/hymn-maker uses every name of God—harvested from throughout the Bible—and every saint’s virtue. And then he endeavors to “bind” all these things to himself, to his heart, so that his own life will be complete, full, and whole, to the extent that it can be.

And, thus, our film, as you might expect from me, is going to explore how landscape helps you read literature and literature helps you see landscapes. And because we’re going to set the words of old prayers and poems within the interlocking patterns and designs of modern cinematography, we’ll be making a kind of digital illuminated manuscript, doing for our century (via film) what the Lindisfarne Gospels theirs.

Tha means a lot to me. Thanks!

Thanks a lot! As soon as you speak into existence, you see and feel it everwhere, don’t you?